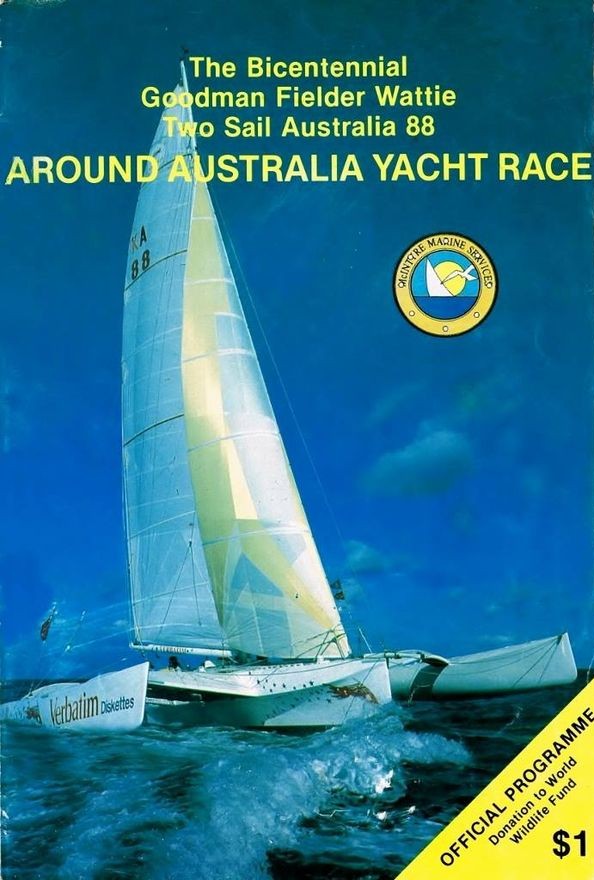

Freemantle to Adelaide – Ian Johnston – Verbatim

Ian Johnston, co-skipper of the 40’ Crowther Trimaran Verbatim recounts a storm the 1988 Around Australia Yacht Race. He and Cathy Hawkins came second in the Race.

This passage was part of a pursuit race around Australia as part of the bicentennial celebrations in 1988. It was billed as the longest coastal yacht race in the world starting in Sydney and going anticlockwise around the entire nation. Each boat was limited to two crew with short fixed-time stopovers in the capital cities. Daily runs were 200 to 350 miles per day for 9000 miles. This turned out to be first and only such competition. Before and after photographs of the competitors showed half the crews’ hair turned grey in the two months of the race! A third of the boats were lost during the race, half did not finish, sadly one of the competitors Geoff Courtis, was killed on the first night along with a sunken police boat. Drama, along with hijinks, occurred throughout the race. Most boats were followed by shore support crews, in constant radio contact through the race.

We had spent the previous two years in full time preparation for this race and left Fremantle as the leading Australian contender in the previous leg, having only lost half an hour from Darwin to the leading New Zealander contender, a 60 foot carbon fibre wing masted trimaran. With a forecast of NW winds increasing to gale force before a storm force SW change. We were in a hurry to drop south and round the formidable Cape Leeuwin before the front screamed in.

Beating out past Rottnest Island I discovered that our generator, located under a canvas in the cockpit, was not producing electricity. Having just had it serviced I was somewhat excited when I radioed Barry, our ground crew at 5pm on Friday and asked him to return to the service centre to get a replacement generator. We would be able to swap it over in four hours time in Bunbury 60 miles south. We needed the generator to power our autopilot, radio, navigation and radar. We could make the passage without it but it would be a slower pace. Our only other motor on board was a 6 hp outboard used for in harbour manoeuvring.

Long story short, Barry eventually rang and suggested to the reluctant, already-at-home-enjoying-a-beer manager that he would find a generous cheque tied to a brick near where a new generator was on display in his showroom window. This elicited a quick, positive response.

A few hours later we sailed into Bunbury and our marvellous ground crew were swinging the new generator on a long rope, along with a much appreciated hot take-away meal, from the end of the first pier in the harbour.

We continued to bash and crash our way south until the dreaded Cape Leeuwin was abaft our beam. The barometer stopped falling and the SW change was heralded with a screaming wall of driven spray.

The wind wasn’t so much the problem compared to the seas.

The NW gale had driven up 25 foot seas but they were being crossed by much larger seas from the SW. Every now and again these waves would cross each other, and there would be a violent upheaval where a 30 foot vertical wall of water would collapse in a welter of white spume. We were sailing “Verbatim”, our 40 foot long, 35 foot wide, 2 ton self-built timber ocean racing trimaran. She had the sail area of a 60 foot keel yacht and had already proven herself as an exceptionally seaworthy, reliable, safe and fast craft. But the next 24 hours was to be our biggest day, our big test. We had planned and prepared for years for this moment. We were towing three sets of drogues on very long ropes to stop our craft from falling down the face of a breaking wave, nose diving and pitch poling , as had happened twice to us before in a smaller, much less suitable craft. We were running downwind with a storm jib tightly lashed amidships to help maintain our direction, average speed 8-10 knots.

In the troughs, it was almost quiet and you momentarily thought that conditions were easing, but rising to the crest and the wind shrieked; you could only breathe in sips for fear of having your lungs emptied in a flash. Our clothing was flapping so violently that it really hurt, goggles were essential to look behind and you had to slither to get around the deck. There was so much wind driven spume that visibility ended at the end of the boat. Yet, it was all under control. No lines were chafing and the drogues provided directional control, stopping the tear away surfs that we did not want. There was a good chance that when conditions eased we could return to full on racing in an undamaged boat. During this time we felt highly charged, with adrenalin coursing through our veins. Everything was bright and clear, we were well rested and everything around us was wildly beautiful. We spoke on the radio to a nearby freighter that had a window on its bridge stove in and Cathy spoke to Macca on ‘Australia all Over’ on Sunday morning during the midst of the storm. Apparently the interview was repeated over successive weeks.

Late that afternoon when we were both in the cockpit with the hatch closed, one of the freak waves thrust up behind us. There was a moments respite from the wind and I looked back at a three story clear blue vertical wall of water that was tilting towards us. For a couple of seconds, we were looking right through the wave at the orange sun, setting in the west. That image is indelibly etched into my memory in the finest detail.

Then, everything went white, heavy and very, very wet.

Such was the force of the water that it knocked the breath from our lungs and drove us into the bottom of the cockpit, gasping for air. Eventually our mighty craft arose from the assault and we could carry on with our race. We finished this leg without any damage; except our generator got wet again.

The technique of running downwind towing a drogue with an unrolled jib, or if more severe, a storm jib lashed amidships, can also be used on keelboats. The drogue should be set far enough behind the boat in such a way that the drogue is within the crest of the following wave, whilst your vessel is on the face of the wave in front. The drogue needs a short length of chain and a swivel to keep it in, rather than on the water.