Don McIntyre, the organiser of the 1988 Race, has lots of info on the 1988 Race on the website:

https://mcintyreadventure.com/adventures/1988-around-australia-race

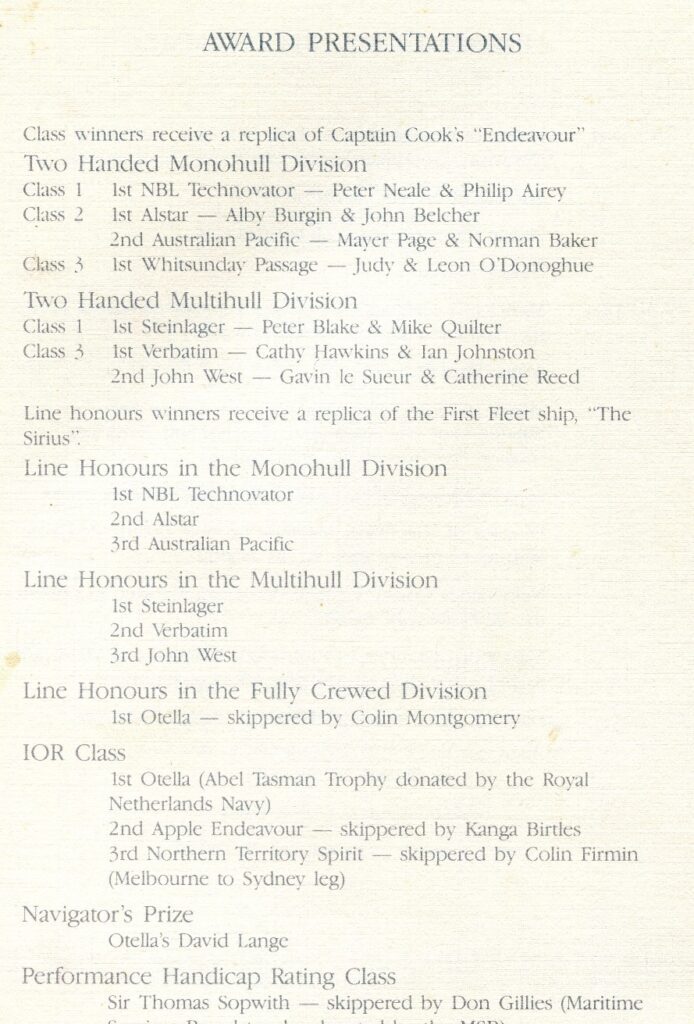

Official Results

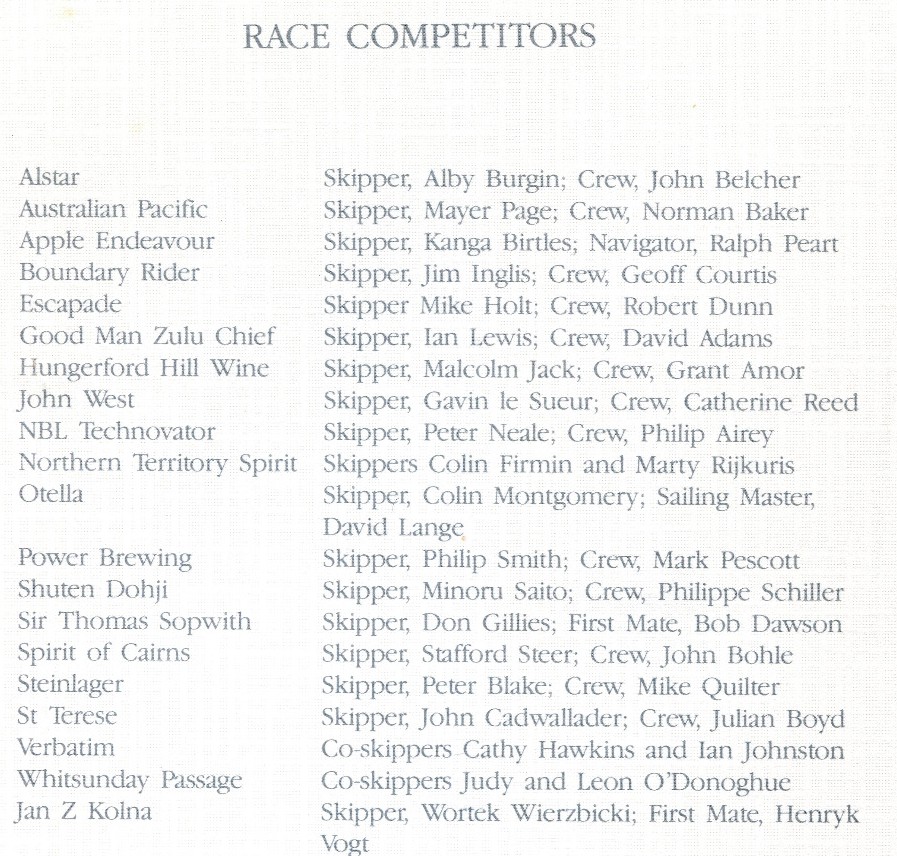

Entrants

Sponsors

Trials of yachtsmen no deterrent in Bicentennial Around Australia Race

Don considers the below story to be the best summary of the 1988 Bicentennial Race.

by TEKI DALTON: Canberra Times (ACT: 1926–1995), Wednesday, 9 November 1988, page 31.

Even though the Goodman Fielder Wattie Bicentennial Around Australia Yacht Race has not yet seen all the competitors cross the finish line, the race “has been a great success” and “all of the competitors had nothing but praise for the organisation and the race concept”, spokesman for the organisers, Don McIntyre, said.

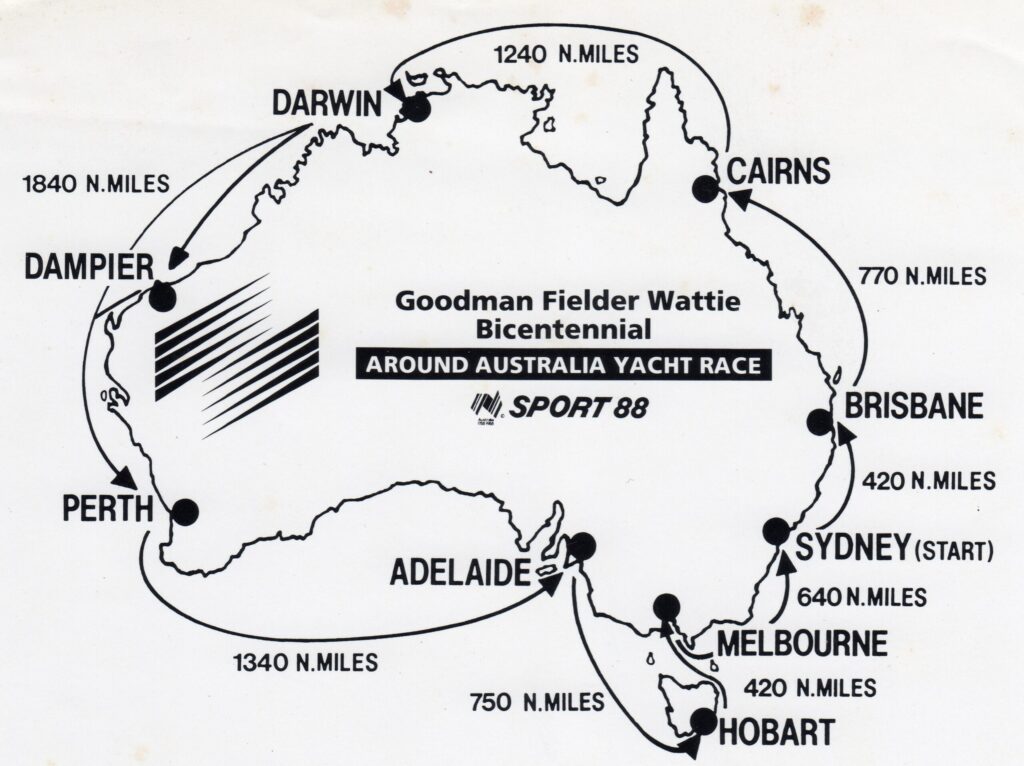

The marathon race really started out as two yacht races around Australia. The first was to be a one-off bicentennial event run by the Cruising Yacht Club of Australia and open to fully crewed boats over 11 m, raced under the corrected-time system as used in the Sydney to Hobart race. There were to be nine stops during the race from Sydney, and these were planned to give the competitors time to repair any damage and replace crew. The stops — Southport, Cairns, Darwin, Dampier, Fremantle, Adelaide, Hobart and Melbourne — were chosen not only because they are the largest centres around the coastline, but because it was hoped that some yachts would be encouraged to compete in one or two of the legs as separate races.

The Canberra Ocean Racing Club was one of many groups interested in putting together a campaign to compete in the race. At the start of 1987, members were wondering how they would find time to enter and how to raise money to cover the considerable cost involved. Twelve months later the same problems were being discussed and, despite an offer to charter Nadia IV (which fell by the wayside), members decided to abandon plans to have Canberra’s flag flown around Australia. Most of the other groups and individuals who had been so enthusiastic at the start soon realised the enormity of the task and they too withdrew, leaving just a handful of competing yachts. The Cruising Yacht Club of Australia was unable to attract a major sponsor to help offset the costs of running the race and felt bitterly disappointed with the poor response from yachties.

But it came to an agreement with the Short-Handed Sailing Association of Australia, which had successfully planned a two-handed race around Australia, due to start on August 8, 1988, to take over the running of the fully crewed race around Australia.

The two-handed race had attracted sponsored entries in both the multihull and monohull sections. Though it was planned as a pursuit race, with competitors required to spend a minimum amount of time in port before starting the next leg, it was felt that many of the boats would be close enough in speed to provide some exciting long-distance racing. As it turned out, it was not so much exciting racing everyone was looking for, but how to survive the tough conditions.

After the first night at sea, the organisers had more publicity than they had bargained for and were facing a barrage of criticism from the media and the NSW Police. During the run up the NSW coast, in strong winds with a moderate following sea, one crew member was lost overboard from the monohull Boundary Rider and a trimaran, Escapade, was overturned. Its two crew members were found clinging to the hull the next morning.

In the fully crewed division, one yacht lost its rudder and returned to Sydney without further damage. To add to the confusion of the night, a police launch from Port Stephens put to sea at the height of the storm in answer to a call, then sank after taking in water through damaged or unsecured hatches. A fishing trawler rescued the crew and returned them to safety.

The next day the police officer in charge of the area accused organisers of disregarding weather forecasts and of encouraging foolhardy competitors to place lives in danger. The race organisers retaliated by stating that the competitors were the ones to decide if they wished to participate in any stage of the race, and that the safety standards imposed on competitors were the strictest in the world.

The week-long mud-slinging did not appear to advance the cause of short-handed yacht racing or enhance the image of some police officials, and it appears the courts will decide who, if anybody, has been wronged.

In the meantime, the race continued, with some boats withdrawing because of crew illness or hull damage, but it was not until the fleet reached the bottom of Australia that conditions stretched the endurance of the crews to the limit. The two final legs, Hobart to Melbourne and Melbourne to Sydney through the Southern Ocean, Bass Strait and the Tasman Sea, were to prove the toughest, and the boats that were among the first finishers in Sydney had some tales to tell.

Steinlager, an 18.3-metre trimaran from New Zealand, was first to finish after 33 days, 17 hours, 42 minutes and seven seconds for the 7,600-nautical-mile race. Skippered by Peter Blake, with Mike Quilter as crew, the trimaran was built specially for this race and is considered to be the fastest ocean-racing catamaran for its size in the world. “We had a horrendous time crossing Bass Strait,” said Blake. “Even on the final night, 60 miles from Sydney, we had doubts as to whether we would finish, as large beam seas engulfed first the windward float, then the main hull and finally the leeward float.”

Blake, a veteran of four Whitbread Round the World races and the line-honours winner with Lion New Zealand in the gale-torn 1984 Sydney Hobart race, is no stranger to endurance sailing. He described the race as the toughest in the world. “There were reefs to dodge, ships and rough seas to contend with, and radical changes in winds because of land masses,” he said. “Because of the coastal nature it was a real marathon and endurance test. We couldn’t relax at any time, and it was the lack of sleep which wore us down in the end.”

Three times during the race Blake and Quilter thought they and the hi-tech trimaran would not make it through. Blake said they had discussed whether it would be better to lock themselves down below and wait for the capsize, or let themselves be flung off the boat, still attached to their safety harnesses.

Blake said the roughest part of the voyage was the leg from Hobart to Melbourne through Bass Strait, when Steinlager was doing 16 to 18 knots over nine-metre waves and was at an angle of 45 degrees. “The waves covered the boat and Mike, who was steering at the time, and the wind just about blew our socks off.”

Second boat across the line was the Australian 12.8-metre trimaran Verbatim, sailed by Cathy Hawkins and Ian Johnston, with an elapsed time of just over 38 days. On the final leg, Melbourne to Sydney, just three miles from Gabo Island, Verbatim lost its rudder and for a while it seemed a case of ‘so near and yet so far’, but they were able to limp to Eden, where their land crew worked throughout the night to repair the damage.

The next boat to finish, and the first of the monohulls, was NBL Technovator, which had been pushed all the way by 73-year-old Alby Burgin’s Alstar. Both yachts missed the worst of the weather which had caused problems for the trimarans, but the boats following them into Melbourne bore the brunt of Bass Strait’s notoriety.

Good Man Zulu Chief, a 15-metre Kel Steinman design sailed by David Adams and Ian Lewis, was only 12 miles from the finish, beating into 50 knots. Problems with steering forced the yacht to turn around and head back to sea to gain sea room, where Adams found the hydraulic steering had gone through the deck. The emergency steering was fitted and they tried for the finish line again, but when about a mile off the western tip of Phillip Island the wind dropped out and they found themselves too close to the rocks. “It all happened very suddenly,” Adams said. “A large wave picked us up and took us about 200 metres on to the rocks. We rolled over, breaking the mast, and we finished up behind the rocks. We spent the next 10 days resleeving the mast and repairing the boat, but in the end we had to admit defeat. We were bitterly disappointed, as we had a lot of people relying on us.”

Another trimaran, St Therese, was disabled off the Tasmanian coast and its two crew members rescued. Attempts to salvage the craft are continuing. The last of the monohulls are expected to finish the epic race this week in time for the official prize-giving in Sydney on November 16, 1988. Don McIntyre is enthusiastic about another around-Australia race in four years’ time and expects a lot more overseas entries. How does he feel about the one just finished? “No regrets,” he says.

Unique Distinction: Sir Peter Blake remains the only official winner of an organised, full circumnavigation yacht race around Australia.

Completion: The race concluded back in Sydney after the fleet navigated severe Southern Ocean conditions and tropical northern waters.

There were a large number of retirements due to severe weather and incidents during the initial legs of the race.